Dear Friends and Investors,

During the first quarter of 2025, the Massif Capital Real Assets Strategy was down 2.1% net of fees, with gross of fees losses from the long book of 1.2% and short book losses of 0.6%. Since the end of the first quarter, the portfolio has been highly volatile. At the time of writing (Tuesday, 4/28), the portfolio is down 0.09% in April; when this letter is sent out on the afternoon of May 1st, the portfolio will be down closer to 4% for the year. The standard deviation of daily returns from April 2nd through April 28th is a little less than 2%, with an average daily return of 0.0%. Put another way, on any given day this month, we have been up or down 2%, followed by a reversal of the same magnitude the next day.

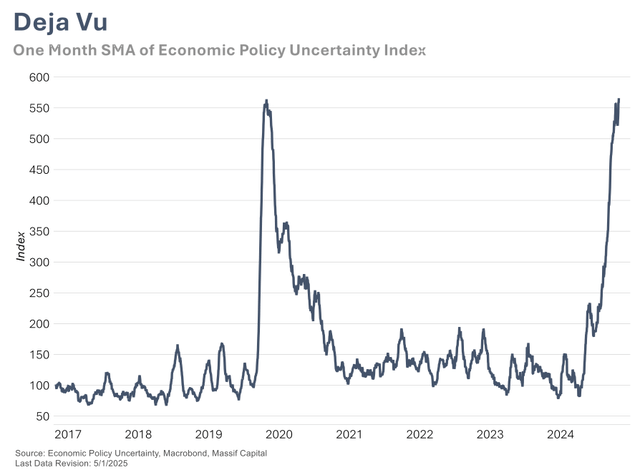

This month’s back-and-forth tendency and the speed at which things change have made writing this letter particularly challenging. Every day has brought a new market-moving headline, which often conflicted with the previous day’s headline. While we do not trade on the news, it has been such a fast-moving environment that forming an opinion about the future of the businesses we invest in and the general investment environment has been incredibly challenging. We tend to look to the past and history as a guide in such situations, but find ourselves in uncharted territory. We would suggest that anyone approaching the current investment environment with a great deal of conviction is deluding themselves and running risks with their investors’ capital that they are unaware of.

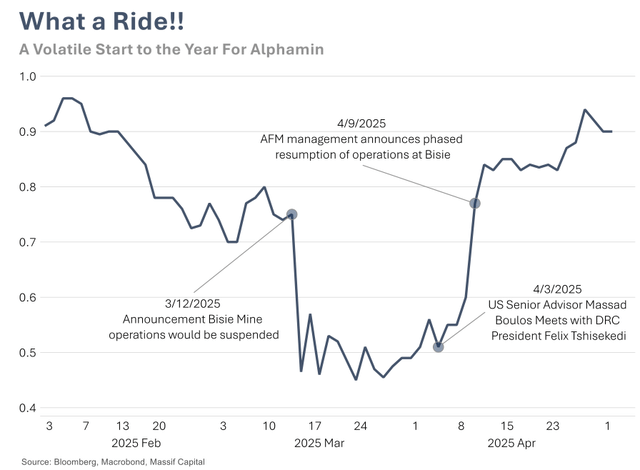

We have long been skeptical of the US political establishment; they talk too much, think too little, and execute poorly. Thus far, that is the second Trump Administration, unforced errors, sloppy communication, and grandiose proclamations about ill-conceived policies. We are flabbergasted by the breadth of disruption (both positive and negative) that President Trump has managed to create in such a brief period. Take, for example, Alphamin (OTCPK:AFMJF), which is not a stock anyone would have ever pegged as one that could be affected by Donald Trump, let alone in his first one hundred days in office.

As a reminder, Alphamin is a single-asset tin miner based out of the DRC. Massif Capital has been invested in the firm for several years, with our first purchase made at roughly CAD 0.40. On 3/12, management announced that they would shut down production at the mine due to rebel activity in the region that was a security risk for the mine. The stock fell dramatically, reaching a local low of CAD 0.45. While annoyed in the short term, we were okay with the price action. We looked forward to doubling our position down 65% from its most recent high, and waiting around two years as the political situation resolved itself and the mine was restarted.

Fast forward to April, and the Trump administration has managed to negotiate a peace/development deal between the government of the DRC and Rwanda, which sees the two often fighting neighbors planning to jointly develop hydropower, national parks, and mineral supply chains throughout the contested North Kivu region of the DRC. To be clear, we are skeptical of the follow-through, after all, the DRC, Rwanda, and the area have been embroiled in conflict for 30 years, but this is the first sign of progress in a long time. Alphamin subsequently announced that they would restart operations, and the shortest politically induced mining shutdown in history was resolved in less than two months. The stock is up 106% in the last 34 days, and while we added on the way down, we were neither in a rush nor added enough.

As anyone following the situation in the Great Lakes Region of Africa can tell you, this outcome was not one that anyone saw coming. The US involvement in the negotiations is itself surprising, let alone that some degree of success was achieved. The US has been in retreat diplomatically from Africa for over a decade, with high-level engagement in Africa by American officials more symbolic than substantive. At the highest levels, US presidents have visited sub-Saharan Africa just twice in the last decade, while Xi Jinping has visited Africa eight times in the previous ten years. That the US somehow negotiated this agreement, not the Chinese, is a significant diplomatic coup. The Trump Administration should be congratulated; if the peace holds, it might not be worth a Nobel Peace Prize, but it should be discussed. Far more people have died in this 30-year conflict than in Ukraine.

This is a positive shock, and we wanted to share it because most of the shocks from the Trump administration have been economically harmful (in our assessment), and we have long said that allowing political bias to taint analysis in investing is dangerous. The critical takeaway is that this administration is unpredictable and will likely surprise at every turn. The next four years will be rocky, volatile, uncertain, and hopefully full of more of this type of surprise than the tariff surprises discussed below, but only time will tell.

As we noted earlier this year, we believe, along with many others, that we are now in a period in which investing from the position of political and geopolitical naivety has ended. As such, what has worked well in markets in the recent past is unlikely to work in the future. The events surrounding the AFM shutdown and restart were the type of events we have been thinking about; that being said, we did not expect the US to pay any attention to events in Africa under the Trump administration, or any administration, soon.

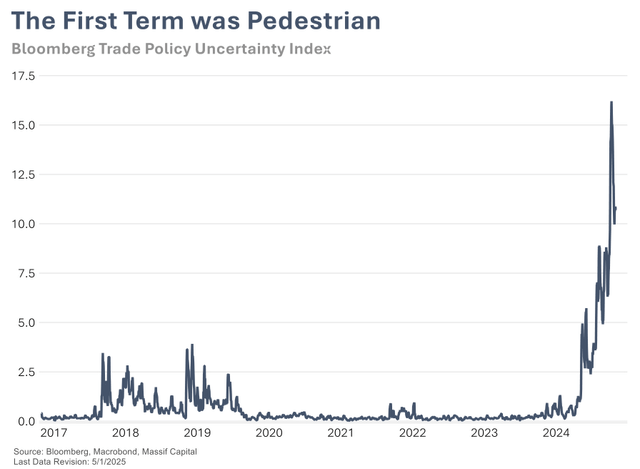

The transition from a period of geopolitical calm to geopolitical volatility has been years in the making. Still, a confluence of events in recent years, starting with COVID and ending most recently with a rollout of an effort by the US government to reshape global trade, has sharply accelerated the transition. This new political-economic paradigm will require investors to adapt fast. Whereas the last three decades have been dominated by globalization, rising trade, and capital liberalization, the next decade will be dominated by the use of trade as a tool of government statecraft and a rapid, disorganized unwinding of a complex system of interdependency. This theme is present throughout the rest of this letter.

Whether or not this unwinding produces the desired outcomes is far from certain. The intricacy of the organically grown international economy is far too complex for anyone to fully understand the secondary and tertiary impacts of the sweeping changes currently underway. In the case of the US, the Trump administration aims to wield geopolitical strength and the US consumers’ endless appetite for consumption like a club to extract trade deals that support increased economic self-sufficiency and reduce trade deficits. Whether they will succeed or not is an open question.

What is less uncertain, in our opinion, is that far from driving the US economy towards a future less encumbered by government, the government is now taking a leading role in shaping our economy. We find little to argue with in Ken Griffin’s recent comment that “President Trump has an incredibly good sense of where the problems lie, but we’re moving too quickly, we’re breaking a lot of glass in trying to solve some very real problems.” We would add that the ability to identify problems does not mean one can also solve those problems.

There is no question in our mind that the idea of “free trade” is a mirage, and that we have continuously operated in a system that was less than free, that is unbalanced, and has unending barriers to the free flow of goods and services. Furthermore, there is little question in our mind that at times the result of less than free trade has been to foist upon people least able to adapt, the burden of rapidly adjusting to changes they could not foresee, and did not understand. At the same time, we cannot allow ourselves to respond to these unfortunate circumstances with a cure that is worse than the disease.

The current path risks replaying some of history’s more disastrous economic policies. The most striking, least discussed, and most uncomfortably rhetorically similar being Latin Americans’ experiment with import substitution. Starting in the 1930s, Latin American political leaders, seeking to extract their countries from what they considered unfair and unbalanced trade relations with former colonial masters, enacted heavy tariffs and domestic protectionism. These policies, known as import substitution, were supposed to lead to manufacturing growth, boost exportable goods, and increase wealth. The policies instead led to protected economies that were globally uncompetitive, rampant inflation, and poverty.

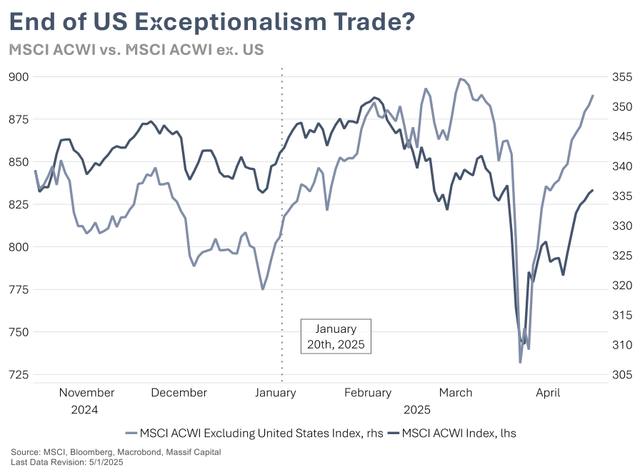

The US is far from that outcome; we are not proposing that the US is on the cusp of becoming the equivalent of a failed Latin American country, but we believe history should serve as a cautionary tale. The current path is slippery, and caution is critical in economic policy because economic reflexivity produces runaway feedback loops outside government control. For investors, there is already the penumbra of disconcerting trends that could spiral in the form of a weakening dollar, falling equity prices, and rising yields. This triple threat is rarely seen outside of emerging markets. It may foreshadow a loss of trust in US economic exceptionalism, a loss that is mirrored in the emerging perception of the US as an unreliable partner by our allies. That trend, while different, is related, as the ability to confront foreign adversaries is linked to the strength of a country’s domestic economy and the breadth of resources it can call upon in a fight. Given the literal scale of the foreign policy challenges the US faces in the form of countries like China, even poorly equipped European allies are essential.1

The loss of trust in US economic exceptionalism has significant repercussions for investors. For at least the last twenty years, US assets have been the winning investment, buoyed ever higher by rising growth, US dynamism, and, at times, especially since 2008, a proactive Fed and profligate government. The resulting shift away from the US presages underperformance for US assets, a painful transition we expect will be most acutely felt by passive equity investors, who have benefited dramatically from the relatively gentle and positive glide path that globalization created for the overly financialized US economy.

US equities comprise 70% of the MSCI World Index and need strong capital inflows to maintain that overweight status; the pain will be significant if those flows change direction. According to a recent report by Bridgewater, discussing many of the same themes discussed here, “US stocks need to attract ~65 cents of every dollar that flows into stocks [globally] just to keep rising.”2

In this environment, it is critical to carefully examine the fiscal policy and political constituencies of the countries one invests in to find opportunities. The global shift underway is not about achieving broad, undirected economic growth but instead restructuring domestic economies to support self-reliance, national security, and aggrieved political constituents (please see our previous discussion of these themes in When Markets Meet Mercantilism). These are specific national goals that will produce specific national and international economic outcomes. Charlie Munger famously said, “Show me the incentive and I will show you the outcome.” That is truer today than at any time in recent memory.

We believe Massif Capital’s investment focus is well-suited to this environment. In an increasingly fractured world, significant investment in natural resources, critical infrastructure, and heavy industry is highly likely if the incentivized goal is self-reliance and national security. Furthermore, if economies worldwide pursue these same goals simultaneously, as they are presently, our opportunity set dramatically increases. Picking winners in this context will not be without challenges, but we believe strongly that being in the right place at the right time is half the battle, and we believe the right place and right time for liquid real assets is the here and now.

Oil and Gas Markets – A good European backdrop, potentially spoiled by the US-China Trade conflict

Our oil and gas exposure remains focused on European producers, specifically those with significant exposure to the North Sea and the Norwegian Continental Shelf (22% of the portfolio). This focus is a function of not only the quality of the companies and their clear discount to intrinsic value, but also the long-held belief that they are the only flexibility in the European energy system. Within the context of a more geopolitically complicated world, we continue to believe that the variable has unpriced value.

At the same time, it is essential to note that the ongoing trade war will have a difficult-to-foresee impact on the marginal cost of natural gas in Europe as set by imported LNG. Before Russia invaded Ukraine, Europe was flush with natural gas, or at least capable of securing as much as needed via pipeline. Furthermore, as the continent had a degree of sourcing optionality for energy, high-priced LNG did not set the marginal price for domestically consumed natural gas. Fast forward, and much of the continent’s flexibility has been lost. While some Russian pipeline gas still flows into the EU from Turkey, the vast majority of the 150 billion cubic meters per annum of pipeline gas the continent used to buy from Russia has now stopped flowing.

European Greens have also had their say, with between 6,000 and 7,000 megawatt hours of coal-fired power capacity shuttered and all of Germany’s Nuclear power. The poorly conceived energy independence many thought renewables would provide has also not turned out to be the panacea that optimists had hoped for. The EU is now left with few domestic resources to help heat homes, power industry, or feed the grid, save for France, where Gaullist 3 tendencies are, for once, proving forward-looking in the form of the continent’s largest fleet of nuclear power stations.

According to the European Commission Quarterly Report on European Gas Markets, EU gas consumption in 2024 was 332 bcm, of which 273 bcm was imported. Thirty-six percent was imported from Norway and the UK, with Norway representing the source of 30% of imports, 10% more than the US exported to Europe. Norway and the UK export as much as the US and Russia to Europe. Norwegian gas is now, in some regards, the sole source of energy in Europe.

Because the marginal bcm comes from LNG, European Natural Gas prices must remain high enough to continue attracting LNG imports. This creates a very favorable production environment for regionally sourced natural gas, given that firms such as Var (OTCPK:VARRY), Equinor (EQNR), and Harbour Energy (OTCPK:PMOIF) can produce a barrel of oil equivalent at well below $20 a barrel, and in the case of Var, as low as $10 by the end of 2025. TTF (European Natural Gas Prices) are trading at a discount to JKM LNG, the leading price assessment contract for spot physical cargoes of LNG delivered into Northeast Asia. The implication is that TTF prices must rise to attract cargoes away from Asia and into Europe. This is good for our investments.

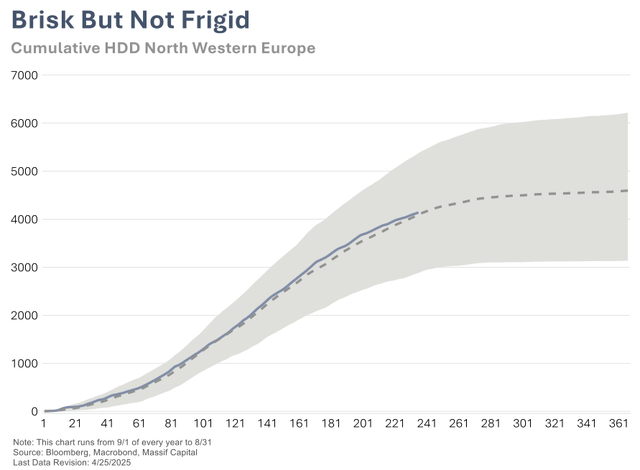

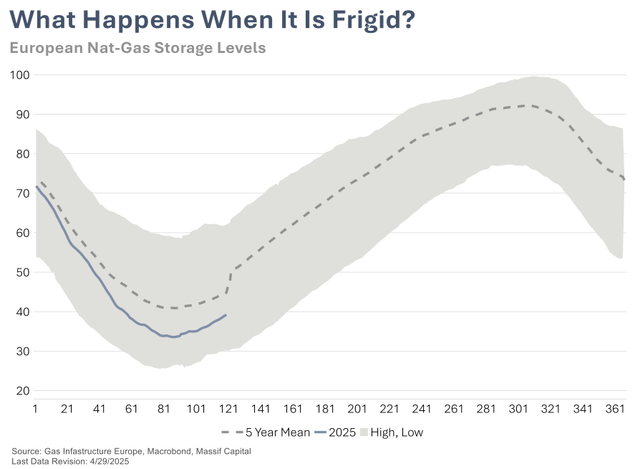

Meanwhile, this winter was not cold in the grand scheme of things, but was sufficiently cold that EU Natural Gas in storage hit its lowest levels since 2022 and 2021. This is a favorable situation to own European Natural Gas producers, especially when the companies are strong competitors, with solid balance sheets, good management, and greater than 10% annualized shareholder returns in the form of dividends and share buybacks.

Nothing escapes the impact of a global trade war, and the favorable long-term picture is muddled by US Tariffs, specifically US tariffs on China, which have had a chilling effect on that country’s consumption of US LNG. Since March, not a single barrel of crude oil or molecule of natural gas from the US has been landed in China. In the first two months of the year, China imported 1.07 million tons of US oil, a 40% YoY decline.

Between 2021 and 2023, Chinese companies signed long-term LNG contracts with US suppliers covering 26.26 million tons per annum of LNG, with about 20.76 million tons per annum scheduled for delivery from 2025 onward, accounting for 25% of China’s total long-term LNG portfolio. Given that US LNG imports into China face a crippling 99% import duty the fact that most of China’s long-term LNG contracts with American suppliers are structured with destination-flexible clauses, allowing buyers to reroute cargoes globally, is going to prove a critical throughout the remainder of 2025, and likely beyond.4

The loss of US LNG in China is not an insurmountable challenge this year, but it becomes more challenging as years go by, which is an essential complication for our discussion of Europe.

Bloomberg New Energy Finance expects China to consume 450 bcf of gas this year, of which 25% will come from LNG. Most of that LNG comes from places like Australia, with only about 4.2 million tons of US-sourced LNG in 2024, with expectations that in 2025, it would be slightly more at 5.7 million tons per annum. This is a manageable volume to replace via spot purchases in an LNG spot market of roughly 145 mt.5 The ramp-up of US-sourced LNG between now and 2030 will make swapping contracted cargoes for spot market cargoes more challenging.

LNG contracts have historically been written without destination flexibility. This is changing, with an increased shift towards a buyer-centric contract structure, an evolution led by US suppliers. We estimate that between 2025 and 2030, most new LNG supplies coming online will come from locations adopting more flexible contracting terms as the standard. However, that is an assumption based on the location of the new supply, not a review of actual contracts. Complicating matters, much of that new supply will come from the US. Put another way, if US-China trade tensions remain elevated for an extended time (our base case), China will need to swap ever more US contracted supplies for non-US supplies in a spot market where the incremental growth is the US LNG volumes China is looking to avoid.

This year, the trade war has, in our opinion, put a ceiling on EU Natural gas prices, but only because the Chinese volumes of US LNG are limited enough that the spot market can handle the needed shifts, and economic weakness will dampen demand. Chinese demand for LNG is not shrinking though; the nature of their demand is just changing. If trade tensions continue, we are likely to see a reworking of the expected LNG flows in ways similar to what we saw with the reworking of global oil flows when the West stopped accepting Russian oil in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In that instance, while no oil was withdrawn from the market, friction costs associated with reworking global trade created tensions that helped keep oil prices elevated. We may see something similar in LNG markets, which is likely a positive for our investments if it should come to pass.

While the uncertainty created by the ongoing trade wars is making the outlook for the future every blurrier, we very much doubt investments in critical assets that build resilience and self-sufficiency for specific geopolitical groupings, in this case, the EU, will be poor investments for any meaningful period over the next decade.

Metals in a Trade War

Our portfolio remains slightly overweight mining firms at 38% of invested capital, divided across 12% invested in gold miners, 10% invested in copper miners, 7% invested in lithium miners, and 9% invested in tin miners. The numbers looked similar two weeks ago, except for our gold allocation, which had reached 25% of the portfolio. We took the recent pause in the gold’s march higher as an opportunity to lock in gains and adjust our exposure to a more sustainable level. From our perspective, gold is probably set to move higher until we start to see central banks stop buying gold, geopolitical risk ease, and the dollar stabilizes.

If only the story were as simple as other metals. The escalating trade war between major economic powers has triggered seismic shifts in global industrial metals markets, cascading effects on supply chains, pricing dynamics, and strategic resource allocation. As the US and China intensify reciprocal tariffs and export controls, critical metals such as steel, aluminum, copper, and rare earth elements face unprecedented volatility.

China’s dominance in rare earth processing and magnet production, coupled with US tariffs on billions of dollars of metals imports, has disrupted traditional trade pathways, forcing industries to reconfigure sourcing strategies.

Meanwhile, retaliatory measures from the EU, India, and other nations are reshaping regional demand patterns, with copper prices remaining high despite impending economic weakness and steel production forecasts revised downward amid supply chain bottlenecks. These developments underscore a broader realignment of global trade networks, where geopolitical strategy increasingly dictates market access and resource security.

Take, for example, the US reinstating and expanding Section 232 tariffs on steel, which results in a 25% duty on all steel imports and raising aluminum tariffs from 10% to 25% with no exemptions. These measures, framed as protection for domestic industries, have triggered immediate retaliation. The European Union responded with counter-tariffs on $28 billion worth of U.S. goods, targeting sectors like polyethylene and automotive components. Canada, the largest steel supplier to the US, is also weighing reciprocal actions, while Asian exporters face reduced access to a key market. In Canada’s case, the general tariffs are probably the key reason why Mark Carney won the snap parliamentary elections held this week.

The tariffs have distorted trade flows, with US steel imports rising 11.4% month-over-month in March 2025 as buyers stockpiled ahead of stricter measures. However, the long-term outlook is still bleak: Fastmarkets revised its 2025 global crude steel production forecast downward by 34 million metric tons, citing trade uncertainty and weakened demand.

The challenge faced by aluminum markets is more severe, while alumina shortages eased in early 2025, US tariffs and EU sanctions on Russian aluminum have tightened overall supply. The London Metal Exchange price hit $3,083 per metric ton in March 2025, a 22% increase year-to-date, driven by speculative stockpiling and EV sector demand. China’s production cap at 45.5 million metric tons has shifted expansion projects to Indonesia and India, where Vedanta’s Balco plant aims to add 435,000 tons of capacity by late 2025. However, rising energy costs and carbon tariffs in Europe threaten to keep premiums elevated, particularly for high-purity aluminum used in aerospace and electronics. Copper, the most economically sensitive industrial metal, is experiencing a rare moment where its price appears driven not by economics, but by a mix of geopolitical and technical factors. The US- China trade war has triggered a seismic reshuffling of global copper supply chains, upending decades-old trade patterns and forcing market participants to adapt to a new era of resource nationalism rapidly. China’s 34% tariff on US copper scrap has severed a critical supply artery, slashing imports from 440,000 tons in 2024 to under 100,000 tons projected for 2025. This abrupt cutoff has left Chinese smelters scrambling, as scrap previously accounted for 30% of their feedstock. On the other hand, the US, which exports 880,000 tons of scrap annually, about half of which went to China, now faces pressure to redirect these flows domestically or to Asian allies.

American recyclers lack sufficient smelting capacity to deal with all the un-exported scrap, so mountains of scrap risk accumulating at ports unless new processing infrastructure emerges rapidly. Unfortunately for the US, rapidly building copper smelters is a pipe dream; permitting alone usually takes 4-5 years. Current smelting capacity can only handle 55% of domestic concentrate production. Recyclers like Aurubis are pivoting to a 50-50 scrap-concentrate mix, betting on circular economy incentives to offset higher costs. Of all the strengths the US has, building things quickly is not one of them. Someone should have explained this to Donald Trump so that regulatory reform to facilitate such things would be in place before restrictions that impact raw material flows came into effect.

China, on the other hand, knows how to build copper smelters. They have built so many, so fast that there has now been a collapse in treatment charges (TC/RCs), which have turned negative, forcing smelters to pay to process concentrate rather than earning fees. This unprecedented squeeze stems from China’s smelting capacity expansion outpacing mine supply growth. The tariff war exacerbates this imbalance by restricting US scrap and concentrate access, pushing smelters toward risky blending strategies with high-impurity ores.

Meanwhile, in Chile, Peru, and the DRC, the world’s three largest producers of copper, China has deepened ties through its Belt and Road investments and secured large percentages of those countries’ output. At least 31% of Chile’s production, 100% of the DRC’s, and much of Peru’s. The US seeks to redirect these flows via Minerals Security Partnerships. All three nations face pressure to increase production, but must do so while navigating US-China tensions that will be difficult to emerge from as a neutral supplier.

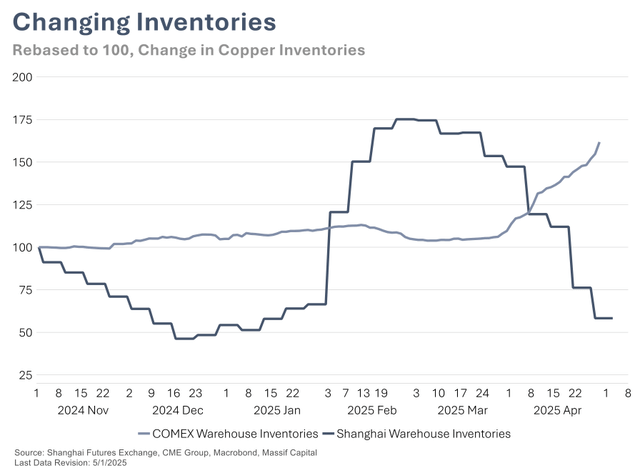

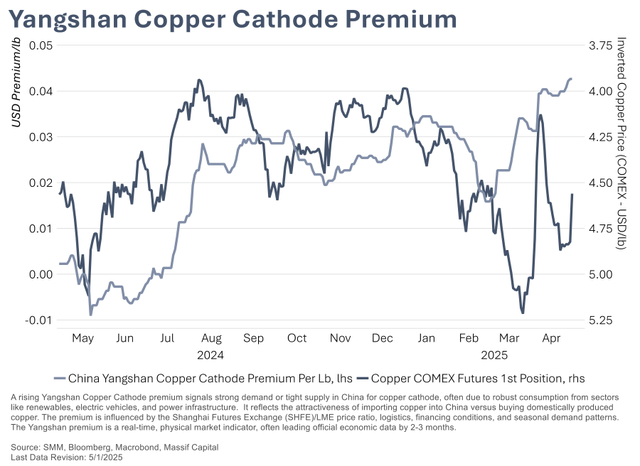

Traders are gaming tariff timelines, creating artificial shortages. Ahead of US import duties, 119,772 tons flooded into CME warehouses – the highest since 2018-while- while LME stocks hit nine-year lows. This logistical reshuffling caused Yangshan premiums to spike to $93.5/ton (0.043 per lb) as Chinese smelters exported refined metal to capitalize on U.S. premiums. The resulting price whipsaw saw copper crash 16% in April 2025 before rebounding on physical market tightness. The geographic arbitrage has also created shortages in China that coincide with decent domestic demand for copper in renewable energy and EVs. As such, China’s domestic stockpiles of copper are dwindling fast, and according to Nicholas Snowdon, Mercuria’s head of metals and mining research, China’s inventories of copper could be depleted by the middle of June.

The rush by US buyers to stockpile copper ahead of potential tariffs, combined with the fall in US scrap imports, is primarily to blame.

The copper market’s center of gravity is shifting from Shanghai to a bifurcated system. CME Group (CME) reports a 300% increase in U.S. copper futures trading since 2024, while LME volumes have stagnated. Physical premiums now vary wildly by bloc- $500/ton in the U.S. vs. $80 in Europe- creating arbitrage opportunities that reshape trade routes. As smelters in Indonesia and India add 1.2 million tons of capacity by 2026, a new multipolar copper order is emerging, defined not by efficiency but geopolitical alignment.

The current trade war has irrevocably altered industrial metals markets, privileging resource nationalism over most other considerations. While US tariffs in theory provide short-term protection for domestic industries, they have also fragmented global supply chains, inflated production costs, and stifled innovation. For policymakers, the path forward lies in balancing strategic autonomy with multilateral cooperation, expanding critical mineral partnerships while avoiding zero-sum trade practices. For industries, survival hinges on agility: diversifying suppliers, investing in recycling infrastructure, and pioneering material-efficient technologies. As the U.S. and China entrench their positions, the metals trade’s new normal will be defined not by free markets but by the relentless calculus of geopolitical competition.

Within the context of this rapidly changing metals market, we remain committed to investing in tier one assets built by tier one operators. At the same time, the opportunity set has expanded, with US assets now being credible opportunities. With that in mind, we have started building out our exposure to US copper developers, with early success in Ivanhoe Electric (IE), which has received a proposal from the Export-Import Bank of the United States to finance the development of the firm’s Santa Cruz Copper Project. The critical variable here, in our opinion, is the people involved. In the future, especially in the United States, one wants to ask: can this management team call up the White House and get the President or someone below the President on the line?

As always, we appreciate the trust and confidence you have shown in Massif Capital by investing with us. We hope that you and your families enjoy the final months of summer and the start of fall. Should you have any questions or concerns, please do not hesitate to reach out.

Best Regards,

William M. Thomson

|

Opinions expressed herein by Massif Capital, LLC (Massif Capital) are not an investment recommendation and are not meant to be relied upon in investment decisions. Massif Capital’s opinions expressed herein address only select aspects of potential investment in securities of the companies mentioned and cannot be a substitute for comprehensive investment analysis. Any analysis presented herein is limited in scope, based on an incomplete set of information, and has limitations to its accuracy. Massif Capital recommends that potential and existing investors conduct thorough investment research of their own, including a detailed review of the companies’ regulatory filings, public statements, and competitors. Consulting a qualified investment adviser may be prudent. The information upon which this material is based and was obtained from sources believed to be reliable but has not been independently verified. Therefore, Massif Capital cannot guarantee its accuracy. Any opinions or estimates constitute Massif Capital’s best judgment as of the date of publication and are subject to change without notice. Massif Capital explicitly disclaims any liability that may arise from the use of this material; reliance upon information in this publication is at the sole discretion of the reader. Furthermore, under no circumstances is this publication an offer to sell or a solicitation to buy securities or services discussed herein. 1 One should never underestimate the scale of the challenge posed by one’s enemies, especially when they have proven themselves, as China has, for example, to be cunning operators. Note that the word enemy in relation to China is a specific word choice, not a flippant one. China and its social and economic model pose a very real and legitimate threat to Western Democracies of all flavors. 2 https:// www.bridgewater.com/research-and-insights/global-economies-converging-on-equilibrium-confront- a-geopolitical-regime-shift 3 Gaullism is the French political philosophy based on the thinking of Charles de Gaulle, at its core is a belief in the criticality of France being able to “guarantee its national independence” and the necessity of self-sufficiency. 4 Research indicates that most contracts are structured on a FOB Origin basis, meaning that the buyer (the Chinese firm) takes title and risk at the US export terminal and is responsible for arranging and paying for shipping, insurance, and all costs beyond the point of loading in the US 5 The International Gas Unions 2024 World LNG Report reported that total global LNG trade was 414 mt in 2024, of which 35% of global trade was transacted in the spot market. |

Original Post

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Editor’s Note: This article discusses one or more securities that do not trade on a major U.S. exchange. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.

Read the full article here